This piece by Pamela Clemit was first published in the Idler, No. 66 (May-June 2019), 73-7:

Anarchy in the Nursery: William Godwin’s Juvenile Library

William Godwin (1756-1836) is known for his anarchist magnum opus An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), a guide to alternative living which still resonates today. He had a second life, less familiar but no less influential, as a progressive educator and author of children’s books.

In the late 1790s, Godwin’s philosophical teachings were felt to be so dangerous that the conservative press launched a popular campaign to discredit them. By the end of the decade, his name was associated with sedition, atheism, and sexual immorality. Godwin took the long view. He looked for other ways to continue his life’s work.

Awakening the mind

Before he morphed into a revolutionary philosopher, Godwin had spent five years as an Independent (Congregationalist) minister. He had been educated by the luminaries of rational dissent, the troublemaking, heterodox wing of English religious nonconformity. Inspired by them, he regarded children as rational beings entitled to exercise their own judgement.

In The Enquirer (1797), a collection of essays on education, manners, and literature, he wrote:

There is a reverence that we owe to every thing in human shape. I do not say that a child is the image of God. But I do affirm that he is an individual being, with powers of reasoning, with sensations of pleasure and pain, and with principles of morality … By the system of nature he is placed by himself; he has a claim upon his little sphere of empire and discretion; and he is entitled to his appropriate portion of independence.

Having written about children, he now began to write for them. Books for tots were all the rage. Together with his second wife, Mary Jane Godwin (they married in 1801), he launched a bookshop and publishing imprint dedicated to educational books. In writing for the young, he achieved a success even greater than in his works for adults.

The bookshop

The Juvenile Library opened for business at Midsummer 1805 in Hanway Street, an alley off Oxford Street, with a loan of £100 from a rich friend, Thomas Wedgwood. To avoid controversy, the Godwins registered the firm in the name of their shop manager, Thomas Hodgkins. In May 1807 they sacked Hodgkins for petty theft, moved to larger premises at 41 Skinner Street, Holborn, and re-registered the firm in Mary Jane Godwin’s name.

Godwin and Mary Jane were in it together. She had practical experience from working as an editor for Benjamin Tabart, a popular children’s publisher, and from her canny negotiation of financial provision for her illegitimate daughter, Clara Mary Jane (Claire) Clairmont. She oversaw book production, the shop, and ‘the produce of the till’. Godwin wrote books to sell and begging letters to keep the business afloat. It is a measure of the regard in which he was held that he was able to call on the great Whig aristocrats, nearly all of whom paid up. The Juvenile Library flourished for two decades, supported by Godwin’s wealthy political friends. Who owned the Skinner Street premises was unclear — the original developer had sold the property by lottery — so Godwin lived rent-free for more than ten years. The accumulated debt helped to bring down the firm in the great financial crisis of 1825.

The Skinner Street salon

The Skinner Street bookshop stood on a corner site with fine bow windows in two directions. It was a business for bohemians. Upstairs were the living quarters, where the family entertained. There was a constant stream of friends, acolytes, aspiring writers, exiles, and émigrés. Lodgers came and went. ‘41 Skinner Street’, the artist John Linnell remembered: ‘a house I never pass without thinking of the evening parties in that fine first-floor room overlooking Snow Hill.’ At the age of sixteen, he became drawing-master to Godwin’s stepson Charles Clairmont, only three years younger than himself.

Visitors were nourished by philosophy and merriment, and the children took part in both. The American lawyer and politician Aaron Burr reported to his daughter Theodosia on some high-minded juvenile pastimes one evening in 1812:

William, the only son of W. Godwin, a lad of about 9 years old, gave his weekly lecture; having heard how Coleridge and others lectured, he would also lecture; and one of his sisters (Mary, I think) writes a lecture, which he reads from a little pulpit which they have erected for him. He went through it with great gravity and decorum. The subject was, “The Influence of Governments on the Character of the People.” After the lecture we had tea, and the girls sang and danced an hour.

The five children in the household had no two parents in common, and three were born out of wedlock. William was the son born to Godwin and Mary Jane in 1803; Mary, born in 1797, was Godwin’s daughter by his first wife Mary Wollstonecraft (who died shortly after her birth), and later the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley and the author of Frankenstein (1818). The other girls were Fanny Imlay, born in 1794, Wollstonecraft’s daughter by the American commercial speculator Gilbert Imlay; and Claire Clairmont, born in 1798, Mary Jane’s daughter by the Somerset landowner John Lethbridge. The fifth child, Charles Clairmont, born in 1795, was Mary Jane’s son by Karl Gaulis, a French-speaking Swiss merchant.

Writing for the young

Some of Godwin’s closest friends wrote for M. J. Godwin & Co., which eventually published around forty titles. Charles Lamb collaborated with his sister Mary on Tales from Shakespear (1807), still a classic; Mrs Leicester’s School (1809); and Poetry for Children (1809). Lamb also wrote The Adventures of Ulysses (1808) and provided verse texts for a series of ‘Copper-plate Books’, including The King and Queen of Hearts (1805), Prince Dorus (1811), and Beauty and the Beast (1811). William Hazlitt came up with A New and Improved Grammar of the English Tongue (1810). Mary Jane Godwin, who had spent her girlhood in France, spiced up the list by smuggling in French books, and contributed her own translations, including (from German) the first English version of Johann David Wyss’s The Family Robinson Crusoe (1814), retitled in later editions The Swiss Family Robinson.

Godwin was the author of at least seven original works for M. J. Godwin & Co., as well as several abridgements and compilations, all for ‘young persons of both sexes’. For prudential reasons, he wrote under pseudonyms. As ‘Theophilus Marcliffe’, his works included The Looking-Glass. A True History of the Early Years of an Artist (1805), an inspirational account of the Irish Catholic immigrant William Mulready, who had risen from obscurity to enter the Royal Academy Schools at the age of fourteen. Examples of Mulready’s childhood drawings were included in the volume to encourage others: ‘Emulation has a thousand sons.’ Mulready became the Juvenile Library’s chief illustrator, claiming later to have executed 307 designs at 7s. 6d. each. Hand-colouring, which added value, was provided by skilled friends in the book trade, or their teenage children.

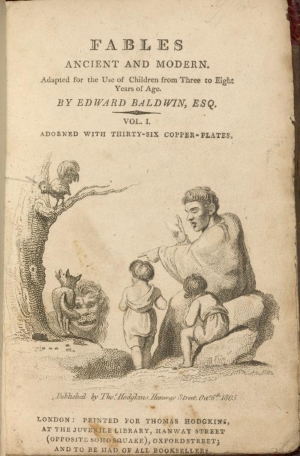

Edward Baldwin, Esq.

As ‘Edward Baldwin, Esq.’, Godwin established a name for himself as a shaper of juvenile knowledge. Baldwin’s most popular work, Fables Ancient and Modern (1805), was a revision of Aesop’s fables with a libertarian spin. In ‘The Wolf and the Mastiff’, the two animals trot along the road together, comparing their lots in life. ‘How fat and sleek you are!’, the lean and hungry wolf says: ‘How do you contrive it?’. The mastiff replies: ‘I bark, to frighten away idle people and thieves; I fawn upon my master, and behave civilly to all the family.’ The wolf is tempted by this life of ease. Then suddenly he asks why the hair is worn away around the mastiff’s neck. The mastiff confesses that his master chains him up and sometimes beats him — ‘But he gives me excellent meat every day.’ The wolf disdains this trade-off and takes his leave: ‘Good morning, cousin! … Hunger shall never make me so slavish and base, as to prefer chains and blows with a belly-full, to my liberty.’

Godwin wrote in the preface to Fables:

Godwin wrote in the preface to Fables:

If we would benefit a child, we must become in part a child ourselves. We must prattle to him: we must expatiate upon some points: we must introduce quick unexpected turns which, if they are not wit, have the effect of wit to children. Above all, we must … render the objects we discourse about, visible to the fancy of the learner.

Fables went through ten British editions by 1824, as well as several in America. A French translation by Mary Jane Godwin appeared in 1806.

Baldwin’s other productions included The Pantheon (1806), in which he subverted Christian morality by talking up the beauties of Greek mythology and featured, to the delight of Leigh Hunt, John Keats, and other school-age readers, images of naked gods and goddesses. (They were clothed in later editions after teachers protested.) Baldwin also wrote three history schoolbooks — of England, Greece, and Rome — treading a fine line between tradition and provocation. In the History of England (1806), he broke the sequence of legitimate succession of the kings and queens of England by including the pretender Perkin Warbeck and the lord protector Oliver Cromwell. Then he dethroned the authoritarian Cromwell in favour of the republican John Milton: ‘Which was the greater man, Cromwel, the politic and successful lord protector of England, or Milton, his Latin secretary?’

Despite questions like these, the political subtext of Baldwin’s schoolbooks was so understated that they were praised by most conservative reviewers, who never questioned the author’s identity. Godwin’s popularity among his former enemies greatly amused the Whig aristocrat Lord Holland:

The good little books in which our masters and misses were taught the rudiments of profane and sacred history, under the name of Baldwin, were really the composition of Godwin, branded as an atheist by those who unwittingly purchased, recommended, and taught his elementary lessons.

When the Juvenile Library went under in 1825, new editions of Baldwin’s works, still under their pseudonym, continued to appear. As textbooks, adopted for class as well as home use, they were studied by generations of schoolchildren who had never heard of Political Justice.

Seeds of intellect and knowledge

Godwin always claimed that he began writing educational books because he could not find any suitable for his own children. A Home Office spy, who reported on the Juvenile Library in 1813, took a different view: ‘It is evident there is an intention to have every book published … that can be required in the early instruction of children, and thus by degrees to give an opportunity for every principle professed by the infidels and republicans of these days to be introduced to their notice.’ The spy may have had a point. In composing reformed versions of popular fables, history-writing, and classical mythology, Godwin was sowing the seeds of the just society he had envisioned in Political Justice. His husbandry aimed to inspire children to think for themselves, to awaken their imagination, and to prepare them for a future of intellectual and moral independence.

None of this could be done overnight. Godwin emphasized the need for cultivation at the child’s own pace. ‘Seeds of intellect and knowledge, seeds of moral judgement and conduct I have sown’, he wrote to his impatient disciple Percy Bysshe Shelley: ‘But the soil for a long time seemed “ungrateful to the tiller’s care.” It was not so. The happiest operations were going on quietly and unobserved: and at the moment when it was of the most importance, they unfolded themselves to the delight of every beholder.’

Festina lente. Nothing could be further from the modern view of children’s learning as testable and quantifiable. Godwin was well ahead of his time. Indeed, our times have not caught up with him.

To subscribe to the Idler, click here.